A Brief History

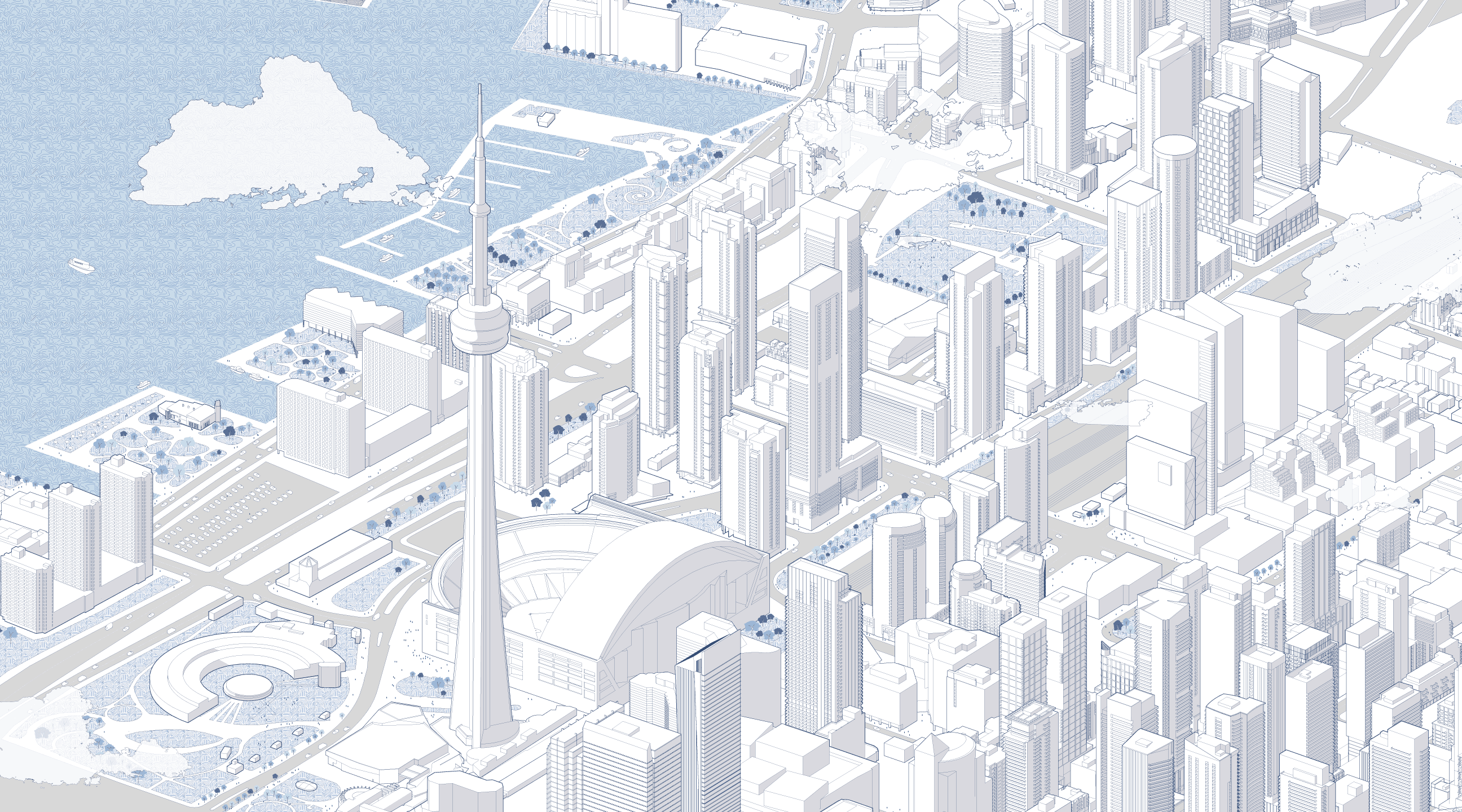

In the past, Toronto has lovingly been referred to as the "City of Homes" considering the bulk of its growth throughout the 19th and 20th centuries was through low-rise, single family neighborhoods. This identity still persists, however the past 50 years has seen a tremendous volume of high-rise condominiums populate the skyline.

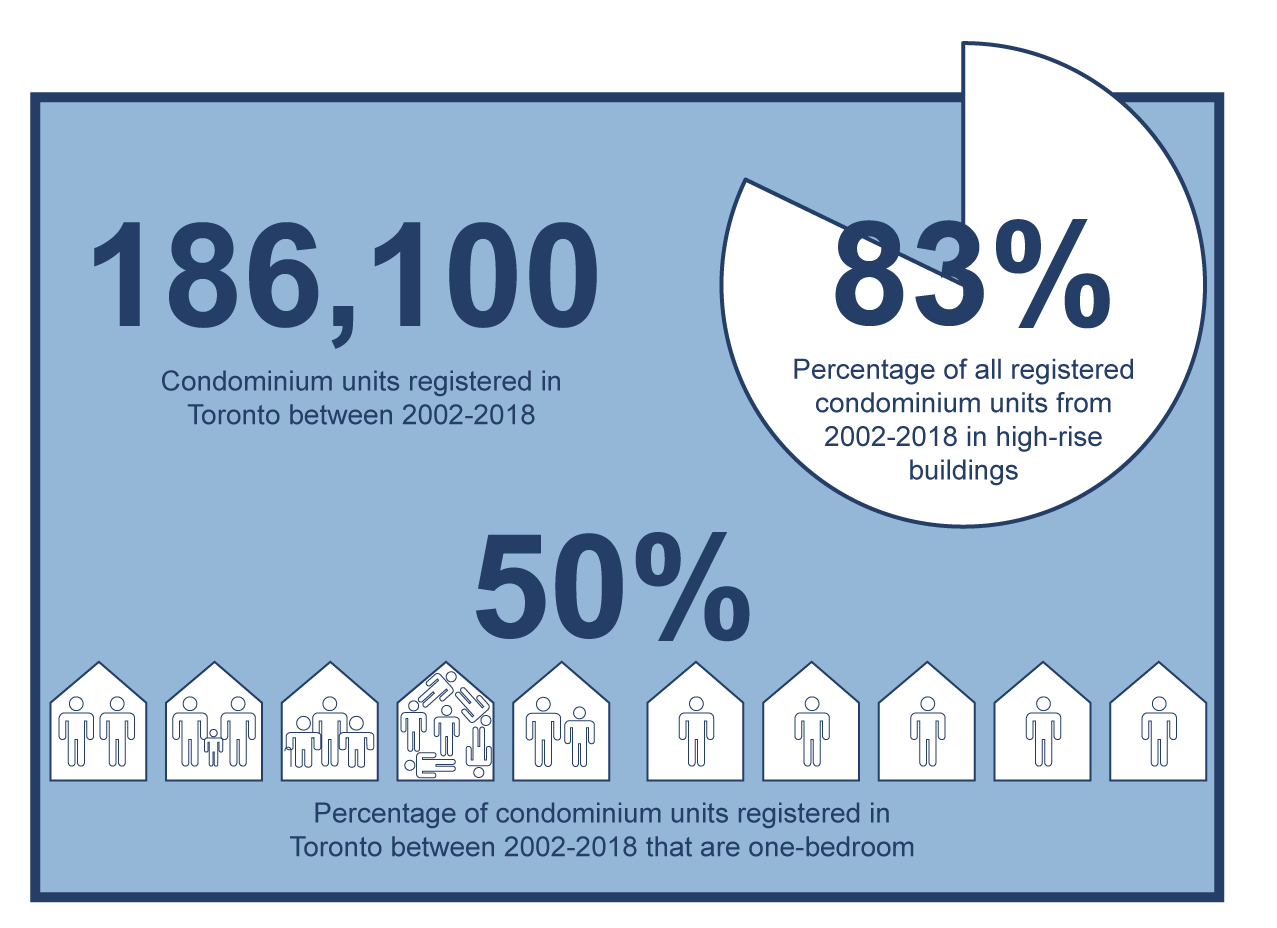

High-rise condominium development from 2002-2018 alone accounts for about 7% of Toronto's total dwelling units. Given that this kind of development has been going on since the 1970's, and continues today, that number is estimated at upwards of 10%.*

*Toronto City Planning reported 154,400 residential condominium units registered between 2002-2018. A CMHC report from 2021 indicated the total number of dwelling units across building types in Toronto to be 2,262,475.

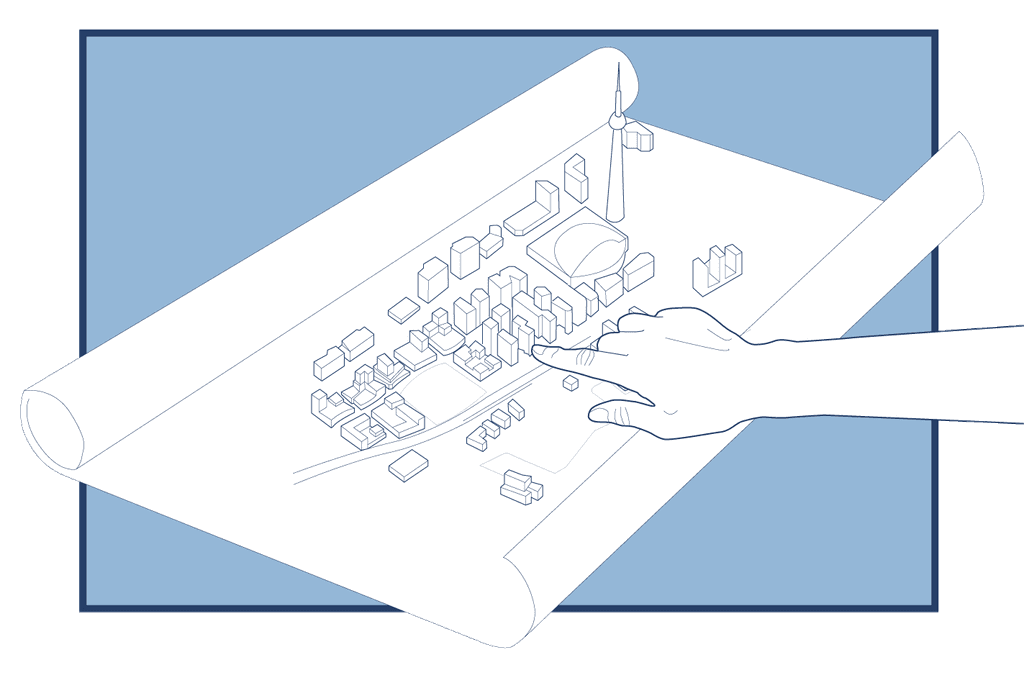

This city's skyline continues to experience drastic change, and regardless of the problems that may result from those changes, we can't afford to demolish and start again. However, if we understand how we got here, we might glean some insight into how to proceed.

The following is a brief summary of Toronto recent history of condominium development, and if you're interested in learning more, 2023's "Condoland" by James T. White and John Punter is an excellent resource.

From Low-Rise Communities to High-Rise Condo's

Many of Toronto's early condominiums were developed in the early-to-mid 20th century. The ownership model was often marketed towards those who didn't want the stresses associated with keeping up their own property, or those looking for to be part of a close knit community, and became an attractive alternative to sole homeownership among older or retired demographics. A condominium doesn't necessarily need to be a new building, or even a single building. Registering a condominium "breaks-up" the ownership of the whole into smaller pieces each owned by different individuals, with a shared stake in the buildings common elements.

Following a mid-century boom of high-rise apartment towers in the city, condominiums started to get registered in similar high-rise buildings, typically with punched or banded window and a largely opaque envelope. Some were initially designed as condominiums, while others were registered at a later date, but a robust federal housing agency was still fueling the development of purpose-built rental across the country.

In the 1980's, looking across the country, Vancouver was experiencing a boom of successful condominium development along its previously neglected waterfront. "Vancouverism" was a term coined to describe this period of revitalization, and the buildings attributed to its success might be familiar to you today. Tall, window-wall glazed towers atop a short podium with townhouses or commercial amenities gained notoriety, and caught the attention of City of Toronto officials.

The developer responsible for the success of Vancouver's waterfront was brought in to work on the large-scale redevelopment of one of Toronto's prominent downtown sites, now referred to as CityPlace. Originally, this site was planned to be funded by the municipality, but the late 1980's and early 1990's were a period of considerable change for how Toronto managed large scale housing projects.

Inviting External Investment

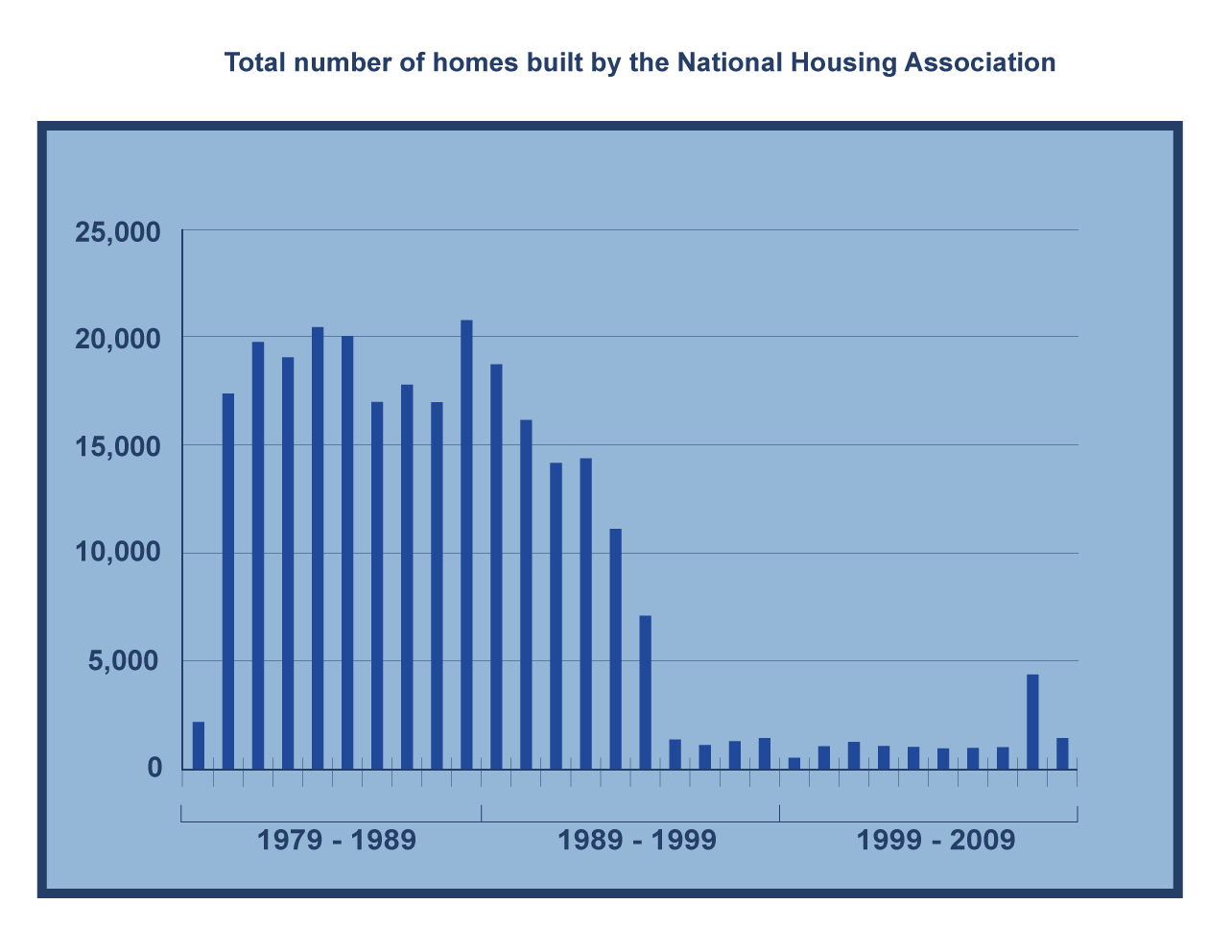

Taking a step back for a moment, Canada has a rich history of development of both market-rate and rental housing. In Toronto, there are many examples of large scale housing infrastructure projects that received funding from federal, provincial, and municipal levels of government, such as the Esplanade housing blocks built between the 1970's and 1980's as part of the St. Lawrence neighborhood plan. However, between 1980's and 1990's, government agencies like the National Housing Association received less funding and fewer commissions.

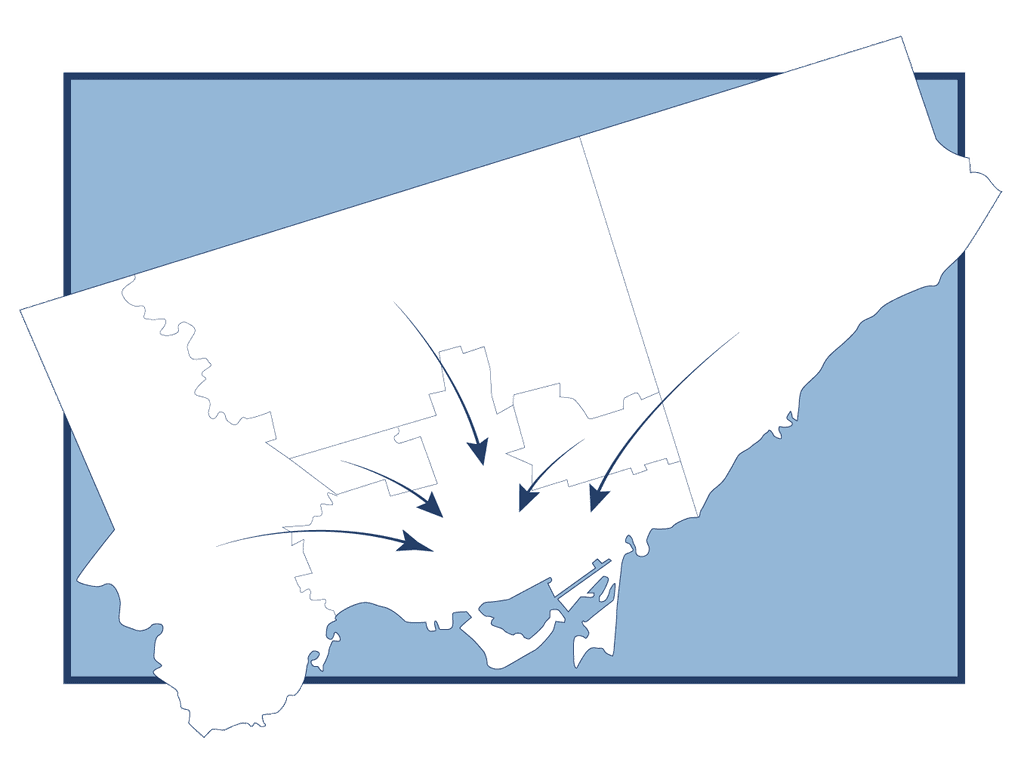

By the late 20th century, support for government housing development began to wane as support for private developments grew. Outsourcing development of new housing would alleviate the financial pressures experienced by government authorities, while still providing new housing. At around the same time, Toronto's six boroughs were moving towards amalgamation, and discussions about how to spend taxpayer money broadened to include the interests and opinions of representatives from York, Scarborough, East York, Etobicoke, North York, and the old City of Toronto. Many of these boroughs brought with them an interest for less government involvement, and support for a higher degree of private investment.

The late 20th century was also a period that saw significant migration of residents back to Toronto, following an influx of residents moving to the outer suburbs in the post-war era. Demand for housing was steadily increasing, and with it came the pressure to build.

Regulating Development

The influx of private development projects in late 20th century Toronto, coupled with support for fewer government regulations, saw new terms of engagement in urban planning. Where government funded development has more control over what gets built and how, private development is required to abide by zoning by-laws outlined in a municipality's Official Plan. These plans dictate the allowable features of new projects, and set-out constraints like the maximum height of a building, minimum unit size, and floor plate depth to name a few. Such by-laws are intended to guide the designs of new buildings to meet larger urban and infrastructural goals. Ontario's Planning Act provides the tools to allow municipalities like Toronto to develop and reinforce their own Official Plans.

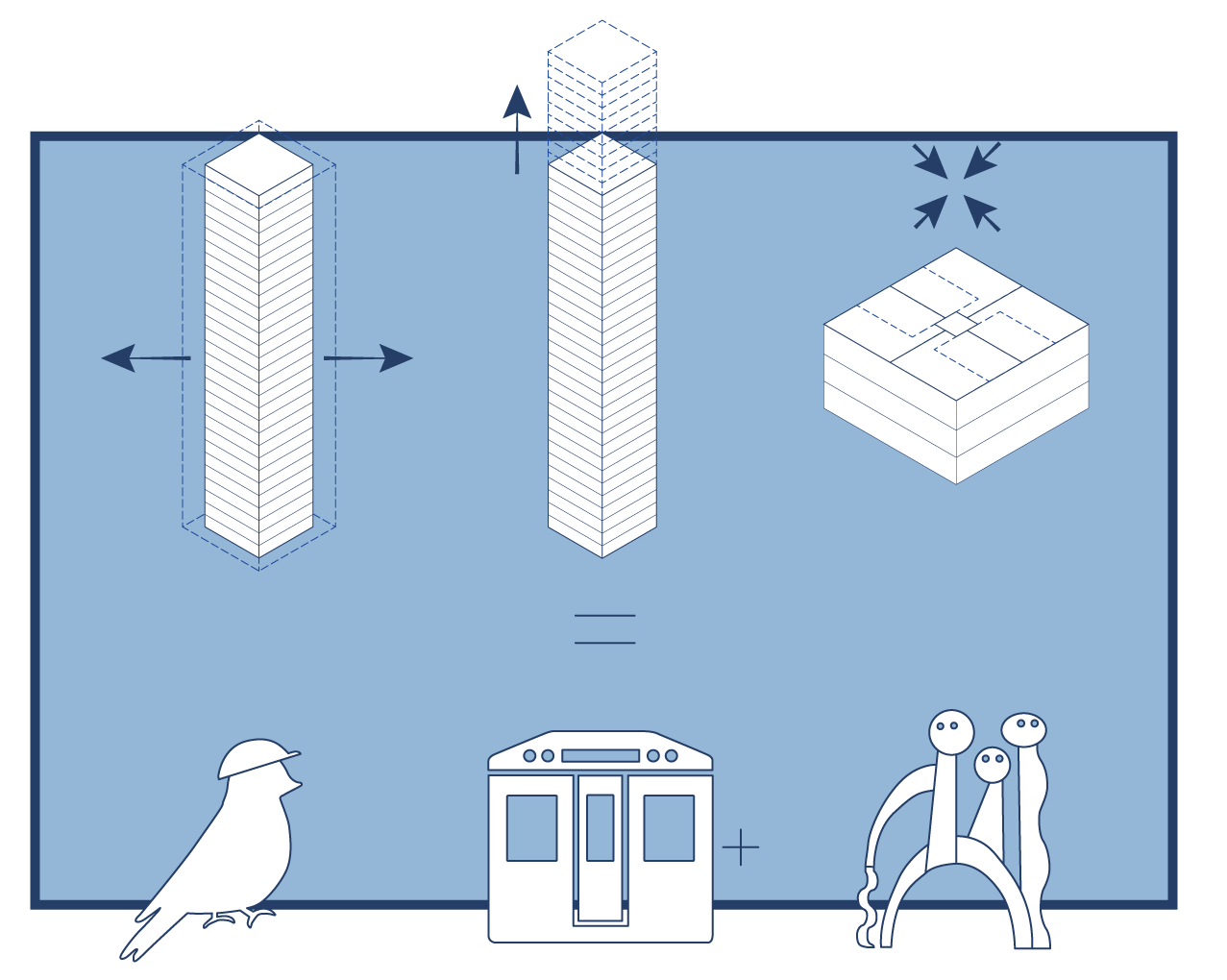

However, not all buildings fit neatly into the predetermined constraints of zoning by-laws, resulting in a need for negotiation between private and public interests. The Ontario Planning Act determines how these negotiations can proceed, and even includes a process for municipalities to set out their urban "wish-list" of public good features developers can refer to. Section 37 of the Planning Act, the Community Benefits Charge, gives private developers an idea of what municipalities want, and allows them to apply for Minor Ordinances - exceptions to Official Plans - for a new development. Features like deeper floor plates, taller buildings, and smaller units than what's outline in the Official Plan can be applied for in exchange for community benefits like improvements to adjacent transit, public art, and bird safety features. Minor ordinances have had a significant role in shaping how Toronto's skyline has changed.

By the turn of the century, private development of housing in Toronto was commonplace, and the terms of engagement for land use planning gave developers clear pathways for new projects. Purpose built rentals were less popular than condominiums, as the former model allowed the building to be bought, owned, and largely managed by the condominium following substantial completion of construction.

Ownership of a condominium unit also became more desirable for first-time homebuyers as single-family homes gradually became more expensive. For some, a condominium unit was the first step towards another home purchase in the future, while for others it represented a place to settle down indefinitely, though trends of increasing property values lent itself towards attitudes of the former.

Arguably, the demand for profitable units may have been a critical driver towards a greater proportion of one-bedroom and bachelor units in new developments. Half of all registered condominium units built between 2002-2018 were one-bedrooms. The vast majority of condominium construction during this period were also high-rise buildings.

Toronto Today

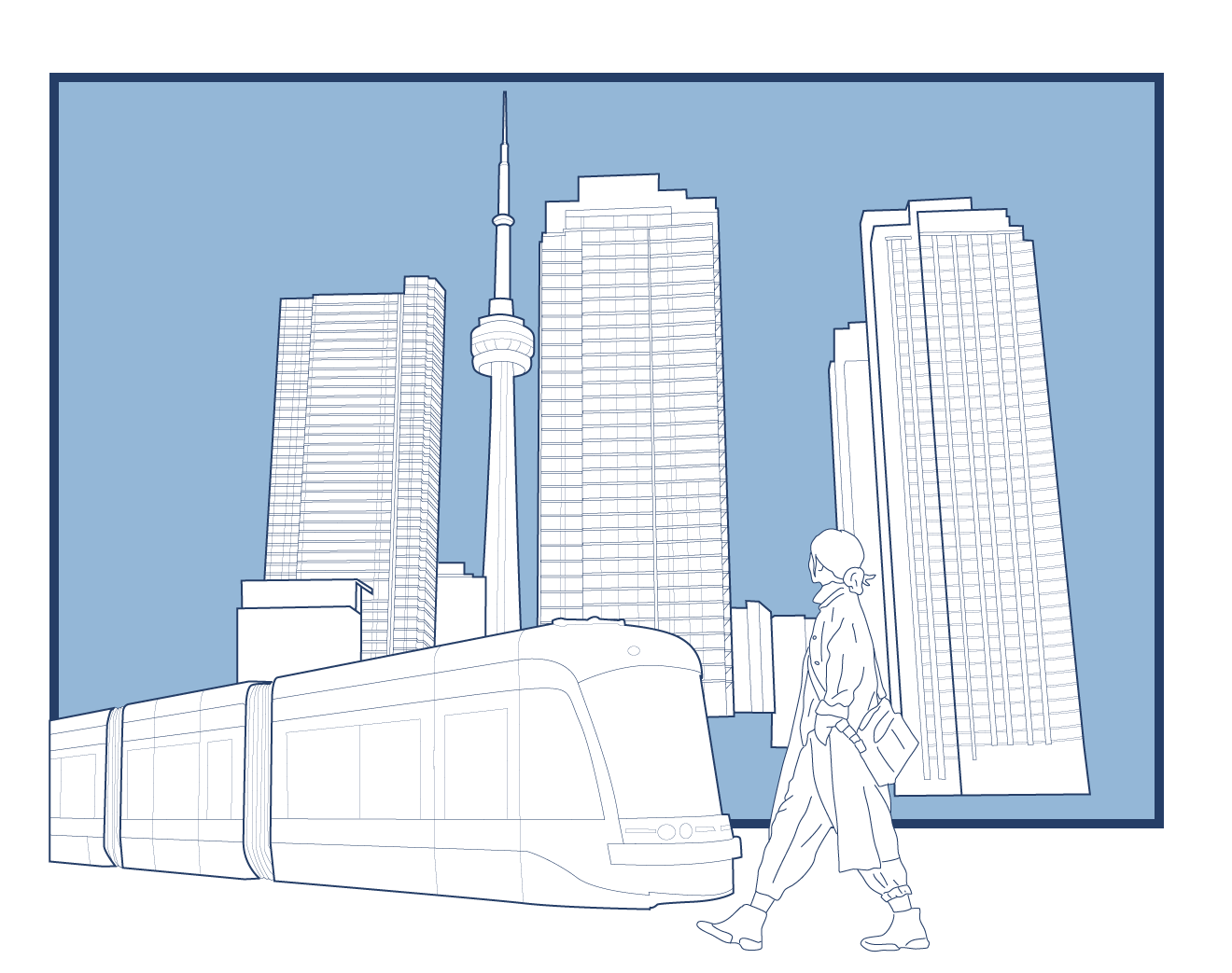

The trend of high-rise condominium development has continued beyond 2018, and while the future is uncertain, the past has left us with a large number of these buildings. Alongside the financial trends that favor condominium development, aesthetic trends continue to favor the style of building adopted by the "Vancouverism" model of development from the 1980's. Fully glazed, window wall systems have been commonly applied new condominium developments across the city. Whether this is a result of the city's development history, the financial incentive of using these systems, its familiarity among contractors, or the demand for these buildings, these fully glazed condos will pose serious problems in light of the looming climate emergency.

And these buildings are aging; fast. The condominium model of high-rise ownership relies on the condo board to keep their buildings maintained into the future.